Another Christmas Story

Every year I am asked by family and friends what do I want for Christmas? My standard answer is Peace on Earth and Goodwill toward All! Usually they laugh and say get real or what is your second choice? But I am being serious about my request. We should demand peace in our home, our country, and throughout the world. Many years have passed since that first Christmas; and only God knows how many Christmas’ have come and gone without people somewhere in the world at war.

There was a time when the world was at peace. Two thousand years ago, the Romans had an iron grip on their Empire; the world was at peace—Pax Romana. Outside the little town of Bethlehem, some shepherds were watching their flocks. Suddenly…the angel of the Lord came upon them, and the glory of the Lord shone round about them: and they were terrified. And the angel said unto them, Fear not: for, behold, I bring you good tidings of great joy, which shall be to all people. For unto you is born this day in the city of David, a Savior, which is Christ the Lord. And this shall be a sign unto you; You will find the babe wrapped in swaddling clothes, lying in a manger. And suddenly there was with the angel a multitude of the heavenly host praising God, and saying, Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, good will toward men.

The angelic announcement proclaimed the long awaited Messiah was born; and he would be called Wonderful, Counselor, The mighty God, The everlasting Father, and The Prince of Peace thus fulfilling four ancient prophecies concerning a redeemer, a child, a virgin, and a town (Gen. 3:15, Isa. 9:6, Isa 7:14, & Mic 5:2). About thirty-three years later, Jesus told his followers that they would have peace from God above, but the world would have wars and rumors of wars until he returns (Joh 14:27, Joh 16:33, & Mk 13:7). Few people believed this obscure man’s teachings would come to pass, much less reverberate down through time, altering the course of world history, defeating empires, changing nations, and bringing peace to neighbors.

We have asked: can a war end war? Less than a hundred years ago, some believed the Great War (First World War 1914-18) would be the “war to end all wars.” When the call went out for volunteers in Britain to go to France, men rushed to sign up. They marched cavalierly to the front singing and boasting they would make quick work of the “Huns” (they didn’t). Three years later, when America entered the war, by then the “Great War” was a stalemate. Composer George Cohan wrote the catchy tune that millions of young American boys sang as they arrogantly marched off to war: “Over There.” Of course, the “glory of war” was short-lived and the “Yanks did not quickly dispatch the “Huns”.” And as the song’s ending line roared: “And we won’t come back till it’s over, over there,” didn’t come to pass as many hoped. It was over, but they did not finish it. Twenty years, nine months, and twenty-one days later, the Second World War began. Yet amidst all the bloodshed and carnage of the First World War, a miraculous event occurred that could have brought peace. “In a place where bloodshed was nearly commonplace and mud and the enemy were fought with equal vigor, something surprising occurred on the Western Front for Christmas in 1914.”

Briefly recalling the events leading up to WWI, the spark that lit the fuse for war occurred on June 28, 1914. Austrian Archduke Francis Ferdinand (heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne) and his wife Sophia, were assassinated while riding in a motorcade through the streets of Sarajevo (a part of the Austria-Hungary Empire). Gavrilo Princip, a Bosnian member of the Serbian terrorist group Black Hand, shot and killed them. The assassination provided Austria-Hungary with an excuse to take action against Serbia. The situation quickly escalated and by August 1914 it had pulled in all the major European powers via their complex alliance relationships and the result was the beginning of the First World War: Germany, Austria-Hungary, Turkey and Bulgaria on one side: and Great Britain, France, Belgium, Russia, and Serbia on the other.

On August 2nd 1914, the German Army suddenly invaded Luxembourg and Belgium, hoping to use them as a quick corridor into France. Alas, as the poet Robert Burns mused, “The best-laid plans of mice and men Gang aft agley (often go wrong). And leave us naught but grief and pain for promised joy.” Much to the German’s disbelief, their attack was slowed by the small Belgian Army and stunned by how quickly the British Army (BEF) reached France and Belgium; even more distressing, the Russian Army’s quick advance into East Prussia shocked the Germans. Ultimately, the Germans would press into France, but French, Belgian, and British forces halted their advance before the Germans reached Paris. Unfortunately, the Allies could not drive the Germans out of France and the war quickly became a stalemate. Both sides dug into the earth, creating a new terrifying word in our vocabulary: “trench warfare.” Each side dug miles and miles of trenches with often only 60 yards separating the combatants. This separation brought an even more terrifying word into our vocabulary, as this separation became known as “no-man’s-land.” By the time the trenches were built the winter rains arrived. The rains not only flooded the dug-outs, they turned the trenches into mud holes. Soon, soldiers on each side spent their time dealing with the mud, keeping their heads down, and watching for surprise enemy raids on their trenches.

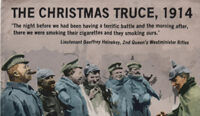

In the early months of the war, millions of servicemen, reservists and volunteers from all over the European continent had enthusiastically rushed to join in the fight: the atmosphere was one of holiday rather than war. Many soldiers believed this would be a quick war. By Christmas Eve of 1914, most British and German soldiers realized this would not be a quick war and they would not be home for the holidays (it would drag on for another four years with 8½ million dead and 21 million wounded). At Christmas time, soldiers on both sides received gift boxes containing food and tobacco prepared by their governments. Germans also sent small Christmas trees and candles to troops at the front. Pope Benedict XV had proposed a Christmas cease-fire, but both sides rejected his proposal as “impossible.” However, the God that works in mysterious ways was about to take the “im” out of “impossible.” Stanley Weintraub, author of “Silent Night: The Story of the World War I Christmas Truce At Flanders Field,” tells us how the “law of unanticipated consequences went to work.”

That Christmas Eve, the Germans set trees on trench parapets and lit candles and began singing carols. Though their language was strange to their enemies, the tunes were not. After the British shot at a few of the trees, they became curious and crawled forward to watch and listen; and after a while, they began to sing. Weintraub says that signboards arose up and down the trenches with the most frequently employed German message being: ‘YOU NO FIGHT, WE NO FIGHT.’ Some British units posted improvised ‘MERRY CHRISTMAS’ banners and waited for a response. More placards on both sides popped up. A spontaneous truce resulted. Soldiers left their trenches, meeting in the middle of no-man’s-land to shake hands. They exchanged gifts: chocolate cake, cognac, postcards, newspapers, and tobacco.

By Christmas morning, the “no-man’s-land” between the trenches was filled with fraternizing soldiers, sharing rations and gifts, singing and (more solemnly) burying their dead between the lines. Soon they were even playing soccer, mostly with improvised balls. On January 1, 1915, the London Times published a letter from a major in the Medical Corps reporting that in his sector, the British played a game against the Germans and were beaten 3-2. Men exchanged gifts and buttons. Soldiers who had been barbers in civilian times gave free haircuts. One German, a juggler and a showman, gave an impromptu performance of his routine in the center of no-man’s-land.

This spontaneous informal truce—which also included some French and Belgian troops—was not to last. After Christmas, commanders on both sides found their troops reluctant to return to fighting and had to order their troops to restart hostilities under penalty of court martial. The Germans replaced most front-line units that took part in the ceasefire. German and British soldiers reluctantly parted, in the words of Pvt. Percy Jones of the Westminster Brigade, “with much hand-shaking and mutual goodwill.” The impromptu cease-fire was largely over by New Year’s Day.

Afterwards, German and Allied commanders tried to cover up the impromptu cease fire. Some generals felt this unauthorized spontaneous impromptu truce was treasonous behavior. Even today, 109 years after peace interrupted the war; French generals still can’t fathom why their soldiers disobeyed orders and joined the German enemy on the silent battlefields for a forbidden Christmas truce. They consider the soldiers’ actions rebellion.

When the British heard the Germans sing a song about a little baby born in a stable, they joined in singing—Silent Night. It’s astonishing how a song about a newborn baby could move men to put down their weapons and embrace their enemies. The Christmas Truce of 1914 remains a heartrending illustration of how common beliefs shared between enemies can make even the bitterest of enemies’ friends. It is a glowing testimony to the words spoken by an angel on that first Christmas so many years ago…Peace on earth, good will toward all. Scottish poet Frederick Niven, in his poem “A Carol from Flanders” wrote: O ye who read this truthful rime from Flanders, kneel and say: God speed the time when every day shall be as Christmas Day. Merry Christmas!

Read a similar story of a “Higher Call”